Brancaster

is a little village on the North Norfolk coast. The staithe is a

gravel track and beach onto a tidal channel which, at low water,

dwindles to a muddy creek winding through the salt marshes.

Sailing is alive and well. The higher parts of

the bank, not quite reached by the Spring tides, has rows of sailing

and rowing dinghies. There is a yacht club, and the yachts are moored in the creek. Across the road is a well-advertised RYA training centre.

The Harbour Master is a laconic, friendly man who clearly knows the creeks and marshes well. He once knew, and sailed with, Frank Dye:

that is testimonial enough for any sailing man. He gave the impression

of ruling his littoral empire with a firm hand: he wasn't going to let Opal into his water until he was sure her skipper knew what he was doing.

East of the moorings, her sail was unfurled. Despite the absence of a boom Opal sails fairly close to the wind. Not as close, obviously, as a Bermudan rigged dinghy, but what she lacks in windward ability she gains in speed. Only in light winds need the sail be fully unfurled.

A little gaff cutter with tan sails (perhaps a Cornish Shrimper?) followed Opal tack for tack, but falling behind. As Opal turned toward the West and over the bar, now safely under several metres of tide, the little cutter sailed N'East to play and tack under the lee of the banks.

The early Autumn sun was warm, the breeze gentle from the N'East. The padded seat was comfortable, the motion soothing.

At the top of the tide a couple of yachts sailed in from the North and across the bar into the channel. Away to the S'East the tan sails tacked across the flat water in the lee of the banks. The wind turbines continued to turn lazily in the haze.

Smoked salmon and pastrami, with grapes. Black coffee. Cold, clean water. A chocolate biscuit. The sea curiously warm. The swell rising and falling like the heaving chest of a sleeping monster.

2 October 2015

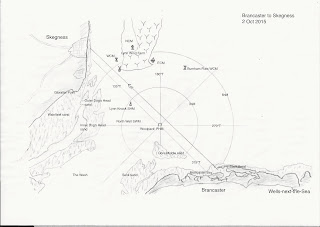

In the August 2015 edition of Practical Boat Owner Andrew Simpson suggested using the Navionics WebApp for harbour planning. It can’t, he suggested, be used for passage planning because it has no lines of latitude or longitude and none of the functionality of the full application.

It does, however, have a scale cursor which can be orientated North-South, or East-West (or indeed any other direction). Perversely, it calls this orientation “Heading”, which it most certainly is not.

The bearing from Brancaster to Skegness is 311°T, a little over 15 miles. There and back might be a decent one-day cruise.

‘Woolpack’ PHM is part way along the bearing line, 6 miles from Brancaster and about 10 from Skegness: well situated at the centre of a GPS web for the little hand-held Garmin GPS.

Opal arrived Brancaster 0900 and was rigged and afloat by 0945. Half a mile down the channel, the skipper realised that the bungs were not tight and that the hull was taking on water. He put ashore to drain the water and tighten the bungs. Was this an omen? A superstitious sailor might have had second thoughts.

Leaving Brancaster was easy: East down the channel through the moorings, North to the channel markers, West to the golf club and then onto a heading of 315°T toward Skegness.

The presence of the wind farm made bearings and headings almost redundant. It was huge, and it's presence dominated the Northern skyline.

The morning shone and the sea sparkled. The slight state of the sea provided a popple which made Opal lively, and the gentle Easterly breeze kept her moving at 4 to 5 knots over the ground.

A white patch on the horizon might have been buildings on the Skegness coast, so was kept on a constant bearing. It turned into a ship, which was not moving, but needed to be avoided. In any case, the SE corner of the windfarm was kept fine on the starboard bow.

The ship became Stril Explorer flying "restricted in ability to maneouvre" above and abaft the helicopter landing platform. Either the tide was pushing hard to the North (bearings on a couple of buoys made this seem unlikely) or she was moving sideways to the South?

A crane on her port side was deploying something that might have been an ROV.

Opal passed her to the South, having found 'Woolpack' PHM exactly where it should have been.

Then a heading of 315°M picked up the Special marker on the SW corner of the wind farm.

Calculation of the tides suggested that Opal should turn for Brancaster at about 1330. In the event (perhaps a mistake) she pushed on until 1400, about a mile and a half from Skegness beach, before turning SE close hauled.

Was this success or failure? The objective had been to reach Skegness: did that mean landing on the beach, or was a mile away good enough?

The skipper didn't really care: it was a wonderful day, he was warm and the boat was behaving beautifully.

On the way back he kept the little boat close hauled, steering between 120° and 150°M: this kept Brancaster on a constant bearing of 140°T. But then the skipper needed to pass water (again!). This meant furling the sail and the complicated ritual with the dry-suit. They drifted downwind, West and a little South, until, when the sail was set again, Brancaster had come to 120°T. Close-hauled and with significant leeway Opal could not now make the harbour on this tack.

The North Norfolk coast is fairly featureless, especially in the gloaming, but a building on the shore looked very like the golf club. The chart suggested it had a lighthouse? At what time would the light be lit? How far East should Opal go before looking for the channel? Which would come first; darkness, the channel or the lighthouse?

As the golf club came abeam darkness fell like a slowly lowered blind. Random red or green lights, sometimes long, sometimes short, often absent, hinted at the channel. Opal crept forward, against the faint breeze, with the tide and controlled by her pedals and rudder. The surf crashed somewhere to starboard (perhaps the shoreline), and a long way to port (perhaps Scolt Head?). Now the channel markers became more consistent. Heading East gradually became heading South and then West. The Staithe ran South from the East-West arm of the channel, but the blind of darkness concealed everything. A yacht, moored in the channel, wisely showed an anchor light at the top of the mast. But it dazzled Opal's skipper and ruined his night vision: the darkness was deeper than it need have been.

The Staithe could not be found and now Opal was too far West and the flood was running fast. Turning East, the Mirage drive made desperately slow progress, and Opal turned into a pool amongst the marsh grass for a pause, a rest and a meal: time to think. And to wait for the moon. She would reveal everything.

As the last quarter rose from the Eastern horizon so did the clouds. Nothing was revealed.

As the tidal stream lessened toward high water Opal again moved East, searching for the elusive Staithe. Five times she ran aground on the marsh grass exposed by the falling Spring tide, and five times the skipper dragged her off into deeper water. He was exhausted. It was 1115, and he had been awake and navigating, by road and by sea, for over eleven hours.

A mooring buoy appeared between the hull and the port ama: he grabbed it, and made fast the painter. Time to rest.

The tiny cockpit of a Tandem Island is perfectly shaped for sitting. The seat can be adjusted to sit upright or to recline. From it the boat can be sailed, paddled or pedalled in complete comfort.

It is the worst place in the world in which to sleep.

Shivering is good; it keeps your muscles working and your body warm. The time to worry is when the shivering stops. They kept shining that light, faint but soul-searching, across his face. Was this some kind of cruel joke to keep him awake as he tried to sleep . . . . ? And that hideous screeching racket, like seabirds fighting over scraps of fish and chips? And the smell of stinking East Coast mud.

Two o'clock in the morning. The seabirds were fighting over worms and shelled things in the mud. The last quarter was shining through the thinning cloud.

With the tide ebbing, and the banks exposed, the Staithe might now be easy to find.

Sitting up and persuading cold, cramped limbs to work was hard, but ultimately successful. Released from her buoy Opal responded to the fierce ebb, being swept along with no chance of entering the Staithe, even if it could be seen. Which it couldn't. Eventually she came to rest on a sandbank, and the water became little chuckling channels which dwindled and dried.

Back to the curled, cramped, confined cockpit.

That light is too bright, but the air smells fresh and clean and the screeching has turned into vigorous honking.

Five o'clock. The Eastern sky began to glow rosy pink and gold. The sand was firm (in places). A fisherman trudged across the estuary, waded through the river and crossed the marsh on his way to his boat. The tide probably turned at five and might lift the boat at seven-ish.

He dragged the Hobie into the river and began to haul it upstream. Every hundred metres or so it had to be pulled across sandy shallows bedded with soft silt (quicksand?).

And finally dawn. And then the Staithe, clear and obvious with all the familiar land- and sea-marks to guide him in.

He pulled the boat up onto the shingle, unstepped the mast, collected the bag of instruments and guided his groaning legs to the car. Removing the dry-suit (he'd worn it for nearly 23 hours) was a profound relief. Comfortable shoes, and then back to the boat. Day sailors were preparing their dinghies and outboards. A small group was helping a newcomer rig his Wayfarer, and park his road trailer. An efficient-looking sailor carried a bundle of boat cover from his dinghy to the clubhouse. The Staithe was waking up to weekend watersport.

At the shingle he watched in disbelieving horror as the Hobie drifted up-channel on the tide.

A group around a Wayfarer confirmed that they had no safety boat to help and would not themselves be on the water for another hour. Two men with an outboard dinghy pondered on where a drifting boat might end up, and whether it would be accessible, and that the channel upstream would be too shallow, and that it might end up neaped on the marsh. Perhaps it would float back on the ebb?

The efficient-looking sailor was just that. He and the Hobie skipper embarked in the tiny dinghy and set off after the errant trimaran. Twice they ran out of water, and had to look for another way. Eventually, with the Hobie entangled in a mooring line just twenty metres away, they stuck fast on a bank. The skipper stripped off his shoes and socks, jumped in knee-deep and ran toward his boat. He was barely 5 metres away when it untangled and drifted off again. And now he was thigh deep in a rising tide.

The efficient-looking sailor had shipped his oars, found a deeper channel and caught the runaway!

As he brought it back the skipper was waist deep and preparing to climb onto a moored boat. Instead he boarded his Hobie, and steered it behind the tiny dinghy back to the Staithe. The efficient-looking sailor brushed away the profuse, embarrassed, inadequate thanks: "You'd do the same for me; I know you would. Anyone who wouldn't isn't worth knowing."

This time he dragged the boat out of the water completely, and up the bank. He ran to the car, hitched on the trailer and hurried back to the boat. It's stern was already in the water! As he loaded it onto the trailer the Wayfarer sailors launched around him, oblivious to the ending of the dangerous drama. The efficient-looking sailor had loaded his passengers into the dinghy and was taking them down-channel to the boat. Saturday morning, and life was perfectly normal.

Back in the car park, he secured the boat, the trailer and the car for the journey home. He was aware that, in his exhaustion, he had made dubious, dangerous decisions. Now everything must be checked and double-checked. Every part and component must be touched and confirmed. Today the sea had teased and then forgiven; the road would not be as friendly.

Even so, he had to stop after half a mile to fasten his seat belt!

At the little cafe the coffee was hot and strong: he drank three cupsful, and then sat in the car to get warm and to let the caffeine do its work.

The road journey was totally uneventful.

She arrived fairly early, to a deserted staithe. As

she was eased onto her trolley, her gear loaded and her mast stepped,

sailors stopped to admire, to comment and to ask. The process of

rigging takes twice as long at the water's edge as it does in her home

driveway. Everyone takes an interest.

Eventually, with the car parked and the trailer padlocked, Opal

slipped into the water. Her wheels were moved from under her keel and

stowed above the stern locker. Her skipper made himself comfortable in

the after seat, and she floated out into the moorings.

The Mirage drive is very deceptive. In calm water like this Opal glides along remarkably quickly. The muscular effort is far less than paddling a canoe or kayak.

East of the moorings, her sail was unfurled. Despite the absence of a boom Opal sails fairly close to the wind. Not as close, obviously, as a Bermudan rigged dinghy, but what she lacks in windward ability she gains in speed. Only in light winds need the sail be fully unfurled.

The channel at Brancaster curves in a long

bend Eastward through Northward and then Westward, widening as it does

so. North of the creek which runs East to Overy, the channel is exposed

to the North Sea. At this state of the tide, about two hours before

high water, the outer banks were covered; the wind turbines turned

slowly in the haze.

A twenty-two foot Jaguar, under engine, turned abaft Opal's stern as she tacked to the North-West, the two crew calling a cheerful greeting.

A little gaff cutter with tan sails (perhaps a Cornish Shrimper?) followed Opal tack for tack, but falling behind. As Opal turned toward the West and over the bar, now safely under several metres of tide, the little cutter sailed N'East to play and tack under the lee of the banks.

Now clear to the North of the bar and the banks Opal

began to feel the short swell of the shallow North Sea. She has a way

of rising to the coming wave, climbing the face, cresting the ridge and

then smacking half of her eighteen feet down into the following trough.

Roughly in the spot where the fairway buoy used to be, Opal's

skipper noted the bearing to the Golf Club and its lighthouse, the

angle of the approach channel and the breakers over the banks to the

East. He furled the sail, broached the coffee flask and opened his

packed lunch.

The early Autumn sun was warm, the breeze gentle from the N'East. The padded seat was comfortable, the motion soothing.

At the top of the tide a couple of yachts sailed in from the North and across the bar into the channel. Away to the S'East the tan sails tacked across the flat water in the lee of the banks. The wind turbines continued to turn lazily in the haze.

Smoked salmon and pastrami, with grapes. Black coffee. Cold, clean water. A chocolate biscuit. The sea curiously warm. The swell rising and falling like the heaving chest of a sleeping monster.

Lunch over, Opal turned South and

East, bouncing over the short swell and then, in flat water, planing

along, windward ama in the air, the hull and l'ward ama fast-skipping

across the ripples. A crossing tack with the little cutter, Opal

passed well ahead and hurtled onward. As the channel curved she bore

away further under the N'Easterly breeze until she was running downwind

toward the moorings. Reefing half the sail did nothing to slow her

progress. Finally, down to a scrap of triangle, she cruised into her

landfall.

Sail furled, Mirage drive out, centreboard and rudder up, and Opal scraped her bows onto the shingle. Her skipper stepped out into inches of water, hauled her dry and unstepped her mast.

Brancaster is a place to visit for a day on the water. Opal

is easy to launch and recover, the staithe is quiet and friendly and

the water is a calm expanse or the open sea. A perfect day out.2 October 2015

In the August 2015 edition of Practical Boat Owner Andrew Simpson suggested using the Navionics WebApp for harbour planning. It can’t, he suggested, be used for passage planning because it has no lines of latitude or longitude and none of the functionality of the full application.

It does, however, have a scale cursor which can be orientated North-South, or East-West (or indeed any other direction). Perversely, it calls this orientation “Heading”, which it most certainly is not.

The bearing from Brancaster to Skegness is 311°T, a little over 15 miles. There and back might be a decent one-day cruise.

‘Woolpack’ PHM is part way along the bearing line, 6 miles from Brancaster and about 10 from Skegness: well situated at the centre of a GPS web for the little hand-held Garmin GPS.

Opal arrived Brancaster 0900 and was rigged and afloat by 0945. Half a mile down the channel, the skipper realised that the bungs were not tight and that the hull was taking on water. He put ashore to drain the water and tighten the bungs. Was this an omen? A superstitious sailor might have had second thoughts.

Leaving Brancaster was easy: East down the channel through the moorings, North to the channel markers, West to the golf club and then onto a heading of 315°T toward Skegness.

The presence of the wind farm made bearings and headings almost redundant. It was huge, and it's presence dominated the Northern skyline.

The morning shone and the sea sparkled. The slight state of the sea provided a popple which made Opal lively, and the gentle Easterly breeze kept her moving at 4 to 5 knots over the ground.

A white patch on the horizon might have been buildings on the Skegness coast, so was kept on a constant bearing. It turned into a ship, which was not moving, but needed to be avoided. In any case, the SE corner of the windfarm was kept fine on the starboard bow.

The ship became Stril Explorer flying "restricted in ability to maneouvre" above and abaft the helicopter landing platform. Either the tide was pushing hard to the North (bearings on a couple of buoys made this seem unlikely) or she was moving sideways to the South?

A crane on her port side was deploying something that might have been an ROV.

Opal passed her to the South, having found 'Woolpack' PHM exactly where it should have been.

Then a heading of 315°M picked up the Special marker on the SW corner of the wind farm.

Calculation of the tides suggested that Opal should turn for Brancaster at about 1330. In the event (perhaps a mistake) she pushed on until 1400, about a mile and a half from Skegness beach, before turning SE close hauled.

Was this success or failure? The objective had been to reach Skegness: did that mean landing on the beach, or was a mile away good enough?

The skipper didn't really care: it was a wonderful day, he was warm and the boat was behaving beautifully.

On the way back he kept the little boat close hauled, steering between 120° and 150°M: this kept Brancaster on a constant bearing of 140°T. But then the skipper needed to pass water (again!). This meant furling the sail and the complicated ritual with the dry-suit. They drifted downwind, West and a little South, until, when the sail was set again, Brancaster had come to 120°T. Close-hauled and with significant leeway Opal could not now make the harbour on this tack.

The North Norfolk coast is fairly featureless, especially in the gloaming, but a building on the shore looked very like the golf club. The chart suggested it had a lighthouse? At what time would the light be lit? How far East should Opal go before looking for the channel? Which would come first; darkness, the channel or the lighthouse?

As the golf club came abeam darkness fell like a slowly lowered blind. Random red or green lights, sometimes long, sometimes short, often absent, hinted at the channel. Opal crept forward, against the faint breeze, with the tide and controlled by her pedals and rudder. The surf crashed somewhere to starboard (perhaps the shoreline), and a long way to port (perhaps Scolt Head?). Now the channel markers became more consistent. Heading East gradually became heading South and then West. The Staithe ran South from the East-West arm of the channel, but the blind of darkness concealed everything. A yacht, moored in the channel, wisely showed an anchor light at the top of the mast. But it dazzled Opal's skipper and ruined his night vision: the darkness was deeper than it need have been.

The Staithe could not be found and now Opal was too far West and the flood was running fast. Turning East, the Mirage drive made desperately slow progress, and Opal turned into a pool amongst the marsh grass for a pause, a rest and a meal: time to think. And to wait for the moon. She would reveal everything.

As the last quarter rose from the Eastern horizon so did the clouds. Nothing was revealed.

As the tidal stream lessened toward high water Opal again moved East, searching for the elusive Staithe. Five times she ran aground on the marsh grass exposed by the falling Spring tide, and five times the skipper dragged her off into deeper water. He was exhausted. It was 1115, and he had been awake and navigating, by road and by sea, for over eleven hours.

A mooring buoy appeared between the hull and the port ama: he grabbed it, and made fast the painter. Time to rest.

The tiny cockpit of a Tandem Island is perfectly shaped for sitting. The seat can be adjusted to sit upright or to recline. From it the boat can be sailed, paddled or pedalled in complete comfort.

It is the worst place in the world in which to sleep.

Shivering is good; it keeps your muscles working and your body warm. The time to worry is when the shivering stops. They kept shining that light, faint but soul-searching, across his face. Was this some kind of cruel joke to keep him awake as he tried to sleep . . . . ? And that hideous screeching racket, like seabirds fighting over scraps of fish and chips? And the smell of stinking East Coast mud.

Two o'clock in the morning. The seabirds were fighting over worms and shelled things in the mud. The last quarter was shining through the thinning cloud.

Sitting up and persuading cold, cramped limbs to work was hard, but ultimately successful. Released from her buoy Opal responded to the fierce ebb, being swept along with no chance of entering the Staithe, even if it could be seen. Which it couldn't. Eventually she came to rest on a sandbank, and the water became little chuckling channels which dwindled and dried.

Back to the curled, cramped, confined cockpit.

That light is too bright, but the air smells fresh and clean and the screeching has turned into vigorous honking.

Five o'clock. The Eastern sky began to glow rosy pink and gold. The sand was firm (in places). A fisherman trudged across the estuary, waded through the river and crossed the marsh on his way to his boat. The tide probably turned at five and might lift the boat at seven-ish.

He dragged the Hobie into the river and began to haul it upstream. Every hundred metres or so it had to be pulled across sandy shallows bedded with soft silt (quicksand?).

And finally dawn. And then the Staithe, clear and obvious with all the familiar land- and sea-marks to guide him in.

He pulled the boat up onto the shingle, unstepped the mast, collected the bag of instruments and guided his groaning legs to the car. Removing the dry-suit (he'd worn it for nearly 23 hours) was a profound relief. Comfortable shoes, and then back to the boat. Day sailors were preparing their dinghies and outboards. A small group was helping a newcomer rig his Wayfarer, and park his road trailer. An efficient-looking sailor carried a bundle of boat cover from his dinghy to the clubhouse. The Staithe was waking up to weekend watersport.

At the shingle he watched in disbelieving horror as the Hobie drifted up-channel on the tide.

A group around a Wayfarer confirmed that they had no safety boat to help and would not themselves be on the water for another hour. Two men with an outboard dinghy pondered on where a drifting boat might end up, and whether it would be accessible, and that the channel upstream would be too shallow, and that it might end up neaped on the marsh. Perhaps it would float back on the ebb?

The efficient-looking sailor was just that. He and the Hobie skipper embarked in the tiny dinghy and set off after the errant trimaran. Twice they ran out of water, and had to look for another way. Eventually, with the Hobie entangled in a mooring line just twenty metres away, they stuck fast on a bank. The skipper stripped off his shoes and socks, jumped in knee-deep and ran toward his boat. He was barely 5 metres away when it untangled and drifted off again. And now he was thigh deep in a rising tide.

The efficient-looking sailor had shipped his oars, found a deeper channel and caught the runaway!

As he brought it back the skipper was waist deep and preparing to climb onto a moored boat. Instead he boarded his Hobie, and steered it behind the tiny dinghy back to the Staithe. The efficient-looking sailor brushed away the profuse, embarrassed, inadequate thanks: "You'd do the same for me; I know you would. Anyone who wouldn't isn't worth knowing."

This time he dragged the boat out of the water completely, and up the bank. He ran to the car, hitched on the trailer and hurried back to the boat. It's stern was already in the water! As he loaded it onto the trailer the Wayfarer sailors launched around him, oblivious to the ending of the dangerous drama. The efficient-looking sailor had loaded his passengers into the dinghy and was taking them down-channel to the boat. Saturday morning, and life was perfectly normal.

Back in the car park, he secured the boat, the trailer and the car for the journey home. He was aware that, in his exhaustion, he had made dubious, dangerous decisions. Now everything must be checked and double-checked. Every part and component must be touched and confirmed. Today the sea had teased and then forgiven; the road would not be as friendly.

Even so, he had to stop after half a mile to fasten his seat belt!

At the little cafe the coffee was hot and strong: he drank three cupsful, and then sat in the car to get warm and to let the caffeine do its work.

The road journey was totally uneventful.

A very interesting account,John, and a salutary reminder at the end!

ReplyDelete