Jeremy Broun is a woodworker, guitar maker, musician, writer and all-round good egg: generous with his time and advice.

His

blog cites his work and his thoughts, and goes into some detail about his approach to woodworking and to life.

He has a YouTube

channel with many videos devoted to woodworking and to his slightly off-beat approach.

Of particular interest is his design for a tiny electric catamaran, for pottering quietly on the River Avon and the Kennet and Avon canal, and which fits entirely inside his Smart car! It would be equally delightful on any canal or quiet river in the country. Perhaps not the tidal Clyde.

Electric boat engines have come a long way since the Thames launches of the mid 19th Century.

Agate herself has a Torqeedo which fits onto the standard outboard motor pad, and has been used on both

Welkin and her tender. More modern motors, carrying GPS, have the ability to hold the boat within a foot or two of a specified position, and can be controlled by a smart 'phone at a distance.

|

| Skipper, Torqeedo and tender |

People worry about the range of an electric boat more than they worry about the range of a petrol or diesel boat. The power density of a battery is far lower than the same weight or volume of petrol or diesel, and batteries take much longer to refill than do petrol tanks.

But, as with all things, range is inversely proportional to speed. The faster you go, the less distance you'll cover on one filling. The slower you go, the longer the pleasure will last.

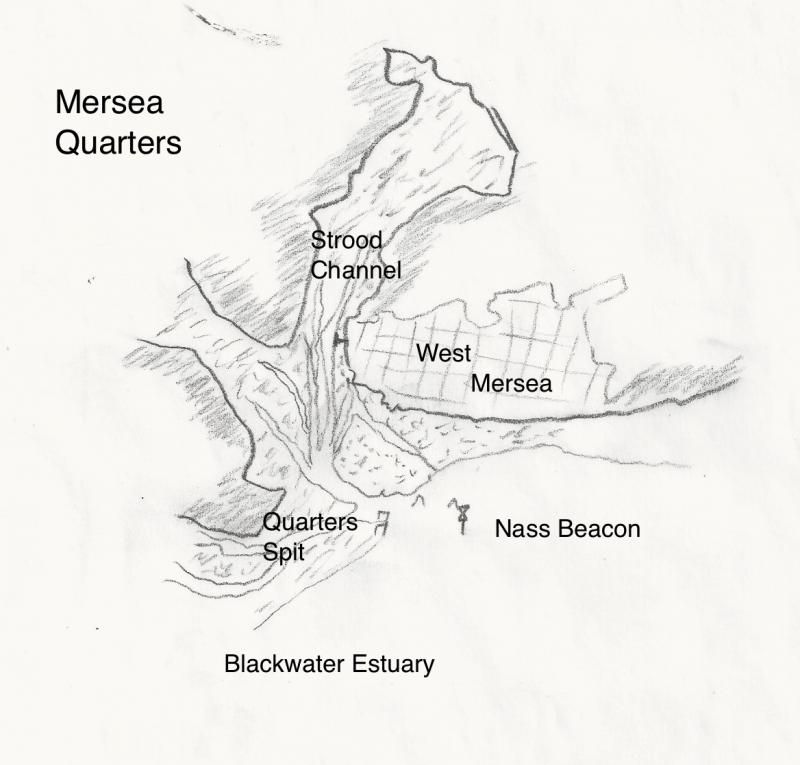

A year or two ago StJohn and his Dad turned up at West Mersea on a cold, cloudless, windless winter morning. It would have been a crime to have shattered the anchorage with Welkin's air-cooled, two-stroke outboard. Instead, they attached the Torqeedo to the tender and, at a silent 2 knots, explored every square inch of every channel and creek. You won't find a noiseless ICE!

|

| West Mersea and the Quarters |

The engine's digital display showed the speed (over the ground), the power consumption, the Kwh left in the battery and how much farther it would take the two intrepid navigators! You don't get that with a petrol tank!

Many skippers had chosen that calm morning to carry out small repairs,

to whip neglected rope ends or to drink tea in the cockpit. t/t Welkin

would glide alongside and silently (and exactly) stem the tide whilst

skippers and mates exchanged pleasantries. You can't do that with a

British Seagull!

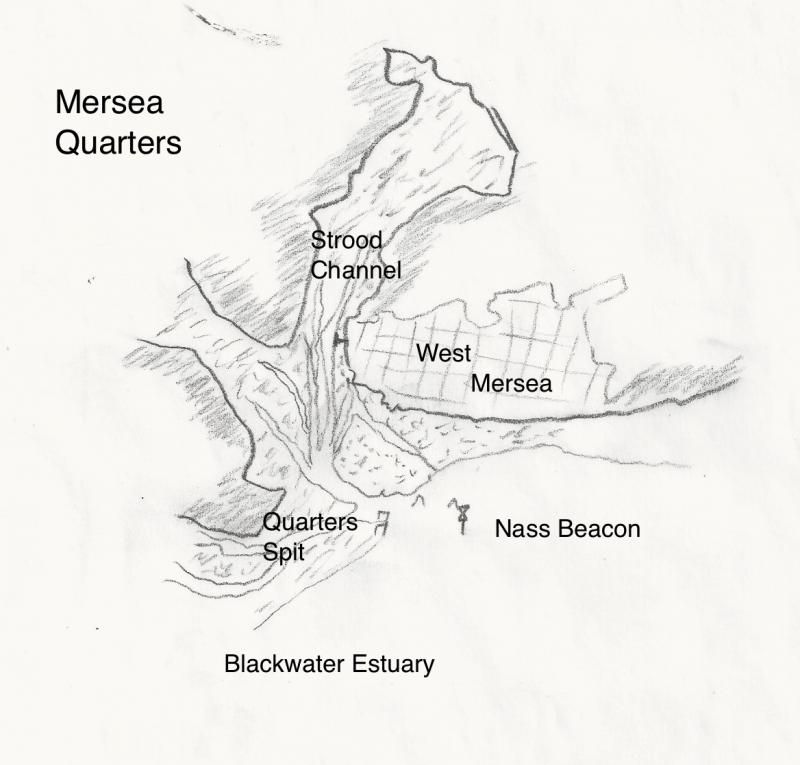

The smacks lay perfectly still at their moorings as our heroes moved quietly around them, seeing the strakes under the paintwork, tutting at the tiny streaks of rust, marvelling at the long bowsprits and admiring the curved, graceful counters. The mirror images shimmered and bobbed in the dinghy's wake, and then relaxed into shining immobility.

|

| CK363 in Strood Channel |

There was almost no conversation; it might have disturbed the birds feeding in the mud, sleeping on the water, floating in the cold, still air. Certainly no need to shout. Without hurry, the batteries lasted all morning.

This could have been the first realization that a small boat is better than a bigger boat.

The definitive moment came a year later, as StJohn rowed the tender

through an angry, turbulent channel in the teeth of the yachtsman's

gale which had prevented him taking Welkin to sea. He was

focussed; concentrating on the oars, the chop, the wind direction,

the tide and his destination. He was the entire boat, at one with his

microcosm, alive in the moment, weighing and accounting every

variable as it changed, moment by moment. Oblivious of his shipmate

and of the world.

At other times StJohn is very aware of the rest of the world. Like Jeremy, he lives in and among the world, carving his own niche, creating his own wake; sometimes across the stream, occasionally at odds with the popular view.

You may not always agree, but they are both worth hearing.